A year later, after adding two new episodes featuring the Cheshire Cat and the Mad Hatter, and with black-and-white illustrations by Punch cartoonist John Tenniel, the book Alice's Adventures in Wonderland was published, with Dodgson using the pseudonym "Lewis Carroll" - the Latin forms of his Christian names.

One hundred and fifty years later, Carroll's "little dream-child" and her companions have become a part of our cultural fabric. My daughters utterly love this book because of its whimsical nature and the sheer chaos of the ideas behind it. Carroll makes no attempt to even construct his chapters - they just effortlessly exist. Alice's Adventures in Wonderland has never been out of print, captivating generations of readers, child and adult alike. It has also apparently been translated into more languages than any other book except The Bible.

One of the reasons for the book's amazing success is that Carroll's main aim was to delight children rather than to educate them. So its awash with parodies of well-meaning cautionary verses, and the usually self-deprecating Carroll thumbs his nose at the moralising tone which was common in books for children at the time. His zany, over-the-top characters, from the nervy White Rabbit, to the bombastic Queen of Hearts and the hyperactive Mad Hatter, are all fantastically realised inventions of an obviously clever and creative mind.

The 150th anniversary is spurning a plethora of versions of this much-loved children's book, including the impressive The Complete Alice, published by Macmillan, the original publishers. From its elegantly embossed white front cover, to the shiny miniature hearts above the page numbers and the hand-coloured reproductions of John Tenniel's illustrations, this is a beautiful and highly collectable tome. And I love the red gold leaves that give it a real sense of special.

As the title suggests, it's a collection of all the adventures : Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and the sequel Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There (1872). The Complete Alice also includes an introduction by Philip Pullman, author of the fantasy series His Dark Materials, along with a selection of letters and introductory pieces written by Carroll for earlier editions. Also featured are the magnificent plates and vignettes of Tenniel's illustrations, coloured by Diz Wallis and Harry Theaker.

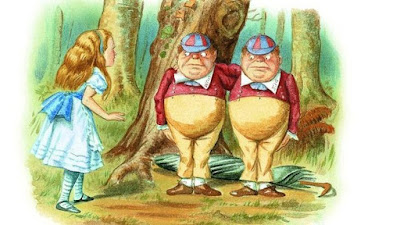

As the title suggests, it's a collection of all the adventures : Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and the sequel Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There (1872). The Complete Alice also includes an introduction by Philip Pullman, author of the fantasy series His Dark Materials, along with a selection of letters and introductory pieces written by Carroll for earlier editions. Also featured are the magnificent plates and vignettes of Tenniel's illustrations, coloured by Diz Wallis and Harry Theaker. Artists been drawn to this classic tale, including surrealist Salvador Dali in 1969. His stylised silhouette Alice floats through a fittingly psychedelic interpretative landscape. But it is invariably John Tenniel's original illustrations, with his contemplative and beautifully drawn Alice, that most people see in their mind's eye when they think of Alice and her adventures.

The book has also inspired some modern children's classics, including The Wonderful Wizard of Oz by Frank Baum, Ethel Pedley's Dot and the Kangaroo and Norton Juster's highly imaginative The Phantom Tollbooth. It has been reinterpreted for stage, television and film, including a silent film in 1903, the classic animated Disney version in 1951, and Tim Burton's darkly exuberant 2010 film, starring Canberra's own Mia Wasikowska as Alice and the inimitable Johnny Depp as the Mad Hatter. No doubt there will be more.

So perhaps now is the perfect time to revisit this classic children's book, sing a verse or two of Twinkle Twinkle Little Bat or recite Jabberwocky, and help celebrate the wonderfully wacky, nonsensical, joyous world created by the sometimes controversial but ultimately enduring Lewis Carroll. I know that my 6 year old has snapped up this edition and insists on reading a chapter a night, such that she treasures the pictures, the stories and the characters. I asked he why she loves it and her only reply was - "because I might have thought of these". Carroll definitely has found his way into the hearts and minds of children, unlike any other author.