Hill tells the story of the mutiny of a number of Japanese officers who try to comit Hara Kiri to protect their honor after capture and instead, are slaughtered by frightened, trigger happy guards, stirred up by propaganda and nativity.

The story is narrated, in a diary format, by school boy Ewen, whose dad works at the camp and was a a soldier in Greece. His humanitarian stance throughout the story a surprising highlight.

Ewen's mates are Clarry and Barry Morris. Clarry suffers from polio. The boys are taught Japanese by Ito, a Japanese officer. From him they learn all about the Japanese camp experience from their point of view - “for us to be prisoner is to be dead person”.

Add to that pressure from American troops seeking intel about Japanese troop movements in the Pacific, the fierce loyalty of the Japanese warriors and their intense pride and hostile reactions from those who have fought the Japanese and been tortured and you have a mixture primed for conflict.

This is a brilliantly written book. Short, punchy. A good size for students and adults to digest. I zoomed through it on a week of train commutes. And the whole account of this tender is sensitively done. It's clear that the boys are the eyes for the reader, but they can't interfere. They are the impartial camera. A very readable novel.

From http://www.nzhistory.net.nz/classroom/incident-at-featherston

The Featherston incident, 25 February 1943

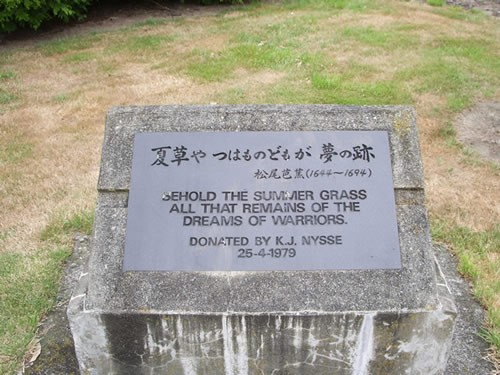

Two kilometres north of the quiet little Wairarapa town of Featherston, a small memorial garden marks the site of a riot that resulted in the deaths of 48 Japanese prisoners of war and one guard. A further 63 prisoners were wounded.A plaque commemorates the site with a 17th-century haiku:

Behold the summer grass

All that remains of the

Dreams of warriors.

Featherston was the site of New Zealand's largest military training camp during the First World War, housing 7500 men, before being dismantled after the war. It was re-established in 1942 to house 800 Japanese prisoners of war.

The riot broke out as a result of some of the Japanese prisoners refusing to work. Capture was humiliation enough for some of these men. News of the riot was kept relatively quiet as a result of war-time censorship. There were fears that the Japanese might retaliate against Allied POWs in Japanese camps. An inquiry was quickly organised in early March and the guards were cleared of any wrongdoing. It pointed to a clash of cultures made worse by the language barrier. The Japanese seemed unaware of the terms of the 1929 Prisoners of War Convention that stated that compulsory work for POWs was permitted; the camp had only a fragmentary translation of this available to the prisoners.

Two of the Japanese officers, Adachi and Nishimura, were found to have stirred their fellow prisoners into action. The Imperial POW Committee in London edited the New Zealand report to minimise any propaganda value that the Japanese government might have gained from the incident. The report claimed that the guards acted in self-defence when charged by a crowd of 250 prisoners throwing rocks. It also noted that the shooting ended as quickly as possible, lasting about 20 seconds.

Others claimed, however, that the actions at Featherston were in retaliation for the mis-treatment of Allied POWs held in Japanese camps. Those who defended the actions of the guards that day were quick to point out that the Japanese prisoners had been generally well fed and housed and that this incident was an exception to the rule. It was noted that the Japanese were in no position to complain about one isolated event for many Allied prisoners fared much worse in Japanese POW camps.

No comments:

Post a Comment