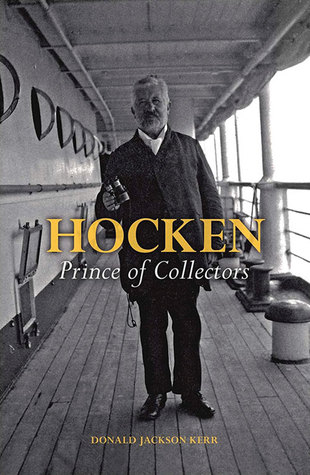

Finally, a really dense, in depth examination of one of New Zealand’s greatest bibliophiles. Kiwis it seemed started publishing very early in the life of the Colony. Not surprisingly, our desire to document and recors, to measure and observe and, of course, express our mind was pretty keen from the get-go. And it’s collections like that at Otago’s Hocken Library that pay a unique tribute to that fact. On my bookcase sits Taschen’s 1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die. I reckon the collection of Dunedin Dr T. M. Hocken would be well over that number. He arrived in Dunedin in 1862, aged 26 and started collecting almost immediately. His collections were vast and specialised, Over about 48 years he’d amassed a huge set of books, manuscripts, pamphlets, maps and sketches on common and rare details of New Zealand’s early history, which he kept at his house “Atahapara” on Moray Place, Dunedin. His original focus was Captain Cook and early exploration narratives of the Reverend Samuel Marsden and his contemporaries; Edward Gibbon Wakefield and the NZ Company; histories of the South; early Maori encounters; and general writing on early NZ’s early histories in general. There are also wonderful maps from Colenso’s expeditions and other early artefacts.

Hocken had two main contemporaries in book collecting: Governor George

Grey and Alexander Turnbull. Biographer

Don Kerr has done a magnificent job not

only documenting the life of Thomas Hocken but he also provides insights into

the intimate life of the man and offers some profiling on the particular difference

between these collectors and their particular collecting habits and drive. For instance, in the forward Kerr notes that

Turnbull was “interested in books as object.

He had them bound and embellished in London by the superstar craftsmen

of the day and built a collection about the history of the book and book arts

around them.” Kerr suggests that Hocken

took a different approach: “...a far more practical approach, developing a

collection primarily as a database to use in e was also a proper book nut: a

bibliographer. His first work on the

subject was A Bibliography o the Literature relating to New Zealand (pub July

1909). It was one of his many

talents. He was a father, an explorer

and a pioneering doctor in the South.

He was well respected in Dunedin and in New Zealand being

employed for a range of unique roles for the colony’s early endeavours. For instance in 1898 Hocken, Kerr tells us, became a commissioner of the Otago Settlement

Jubilee Exhibition, marking 50 years of the province's settlement. A few year’s

later, in 1903, he travelled to Japan, Greece, Egypt, and Great Britain to

conduct his own archaeological and historical research and whilst in Britain,

he collated documents relating to the New Zealand Company and New Zealand

Mission which he brought back to New Zealand.

It’s because of Hocken that we know so much about Marsden and Wakefield and

managed to secure a large number of them and bring them back to New

Zealand. And he continued to be an

educator and promoter giving lectures on a vast range of topics, researched

from his collection. One in particular,

Kerr reminds us, was The Letters and

Journal of Samuel Marsden, now regarded as a pivotal work on the man.

And it all continued throughout his life. In 1010, at his funeral, the entire of

Dunedin turned up to pay respect and not long after the pressure went on to

bring the vast collection under the wings of the Otago University. The Hocken Library became a legacy, valued

well beyond any money. Early leaders William

Pember Reeves saw the value in this amazing archivist and his collection.

Kerr has fully detailed not only Hocken’s life (b.1836-d.1910)

but his collecting activities, and more importantly his legacy to the

intellectual and cultural development of our country. The notes, footnotes and index must be at least

¼ of this 424page tome. They also

include a range of colour plates, photos and images that illustrate the

collection, the times and the topic. Kerr’s

own bibliography for this work is over 30 pages alone! But there’s also plenty of leads for anyone

wanting to explore individual books or writings. This has a massive vault of breadcrumbs for

both professional and amateur researchers to follow – just like Hocken intended,

I think.

And there’s no doubt that Kerr’s the right book geek to make all

this happen. He’s the Special

Collections Librarian and the co-director at the University of Otago’s Centre

for the Book. He’s studied Grey and

intellectuals like, Henry Shaw Frank W. Reed and Esmond de Beer and he’s

already embarking on another project – 12 contemporary Kiwi bibliophiles. Kerr’s created a book that is more than a

biography or a Uni text – it’s a starter for research that could be a catalyst for

your own private collection. Perhaps it’s

a taster to hunt out a few documents at your local antique shop, or to pay more

attention during The Antique’s Roadshow.

But a final question I have for Kerr, as I write this, is this: In the digital age, without the need for bookshelves

how will the bibliophiles of the future collect and what will that be. Is the love of books the same as a love of

reading? Can our personalities and

heritage still be conveyed in what we choose or choose not to read and

store? In other words do libraries and

book collections still matter? What do

you think?